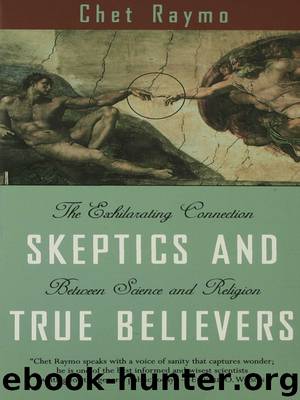

Skeptics and True Believers by Chet Raymo

Author:Chet Raymo

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Published: 2009-09-26T16:00:00+00:00

NINE

Academy in Revolt

The only source of knowledge is experience.

Albert Einstein

ELS A EINSTEIN WAS once asked if she understood her famous husband's theory of relativity. She replied, "Oh, no, although he has explained it to me many times—but it is not necessary for my happiness."

For what, then, is science necessary? ask a growing number of academic critics of science. For most of its history, science has counted on the support of the intellectual establishment while criticism of science has come mostly from religious fundamentalists and literary romantics. One hundred years ago, Andrew Dickson White wrote a big, two- volume History of the Warfare Between Science and Theology in Christendom. He had much to write about, and little has changed since then. Fundamentalist Christians continue to reject "scientific atheism" (or alternatively, "secular humanism") with the old fervor. Even mainline Christian churches still struggle uncomfortably to come to some sort of accommodation with science.

The romantic assault on science was established early in the nineteenth century by Keats (". . . Do not all charms fly / At the mere touch of cold philosophy?") and Wordsworth ("We murder to dissect . . ."), and was amplified by later poets such as Emily Dickinson, Vachel Findsay, e. e. cummings, and others. The gentle needling of science by poets has never been more than a minor nuisance, and in recent times seems to have abated. Fately, however, old intellectual allies have turned against science, attacking the Enlightenment enterprise from inside the academy, in some cases explicitly repudiating the legacy of the Enlightenment and introducing a dangerous new species of ideological True Belief.

Typical of the new criticism is Bryan Appleyard's Understanding the Present, a lively and erudite subversion of science by the sort of fellow one might expect to be a champion of the Enlightenment. Appleyard is a special features writer for London's Sunday Times and the author of several books on modern culture. He is broadly knowledgeable about the history and philosophy of science, and is a nimble rhetorician. Not only is science unnecessary to our happiness, he argues, it is positively inimical to it. "Science, quietly and inexplicitly, is talking us into abandoning our true selves," he writes.1

The editors of Nature, Britain's most influential science periodical, called Appleyard's book an "assault upon reason" and pronounced it "dangerous." According to the editors, Appleyard's slick polemic plays into the hands of those right-wing politicians who blame supposedly novel social ills on erosion of traditional religious values by secular scientific humanism. These are often the same politicians who control the purse strings of science's public support. Nothing pleases them more than intellectual benediction upon their know-nothing reactionism.2

As an analysis of the spiritual malaise of our times, Appleyard's critique of science is provocative but ultimately unsatisfying. Science is intrinsically domineering, all-pervasive, and totally incompatible with religion, he writes. He admits that science is effective, but asks: What does it tell us about ourselves and how we must live? His answer: Nothing. Appleyard recoils from the conclusion, widely embraced within

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Buddhism | Christianity |

| Ethnic & Tribal | General |

| Hinduism | Islam |

| Judaism | New Age, Mythology & Occult |

| Religion, Politics & State |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32558)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31956)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31940)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19083)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14389)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13336)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12026)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5369)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5218)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5095)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4918)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4780)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(4604)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(4532)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4478)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4211)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4109)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(4098)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3965)